The "First Personal Computer" Contest (WIP)

no pedestal lossy.webp)

The KENBAK‑1 computer (officially pronounced "Kenback" by its creator, John Blankenbaker), is considered by some respected authorities to have been "The First Personal Computer". It was released in May of 1971, and slowly sold 44 total units at a relatively affordable introductory price of $750 (about $5850 adjusted for inflation today, in 2024). More than just being the "First Personal Computer", it has been further stated by some (that either don't know better, or are dishonest) that having been the "First", the KENBAK‑1 must have been a very influential machine, paving the way for those that came later, inspiring the Personal Computing Revolution.

However, this is not the case. The KENBAK‑1 did not influence any later technology and made almost no lasting impact on the tech industry. Nor did it make any notable impact on the fledgling personal computer market with its 44 sales. There are no reports of any inspired engineers who later went on to do great things, though given its limited usage in a few schools, it is definitely possible some of the children who used the KENBAK-1 would go on to use more practical systems, enjoyed a career in software development, and vaguely remember the blinking lights of the attractive hexagonal blue box with fondness...

In reality however, the KENBAK-1 would have been very forgettable in the history of computing if not for an event that would occur a generation later, in 1986. Prior to that event, there exist extremely few contemporary references to the machine. One of the very few contemporary references to the obscure machine was written three years after the KENBAK‑1 was first sold, appearing in the February 1974 issue of RCA Engineer Magazine. The article primarily focused on how the newly available "microprocessor chips" would continue to impact the microcomputer industry, but while doing that, unkindly cited the KENBAK‑1 as actually an example of what NOT to do in the future. (Ouch!)

The 1974 RCA publication states: "Prior approaches toward simplified computers appear to be incompatible with microcomputer application goals" with a citation very briefly pointing at the KENBAK‑1 Programming Reference Manual to bolster that statement, apparently requiring no further explanation that the KENBAK‑1 is a clear example of being "incompatible with goals", 'nuff said.[long boring technical explanation]In the context of other things stated in the RCA Engineer Magazine article, I believe the author most likely felt that the KENBAK‑1 didn't support enough instructions, and that the instructions that did exist might have confusing and unexpected behaviours. The lack of support for more formal subroutines perhaps was also considered inadequate, as subroutine support is explicitly lauded as important by the author in the article.

As an example then, the KENBAK's approach towards subroutines is in‑line with existing microcomputers of its time, but quite a bit more obtuse, error prone, and uselessly inefficient compared to the subroutine functionality of the later Intel 8008 and RCA's then‑in‑development 1802 chip, (both contemporary to when the article was written). Those chips were released later, so it's not very fair to compare them to the KENBAK, but it's also to the point where the KENBAK may as well have not supported any structure for subroutines at all, even without considering the later innovations of microprocessors.

On the KENBAK‑1, there is a structure to support subroutines starting with instruction "JMD [XX]" (Jump and Mark Direct to target address [XX]). However, you must reserve a byte of memory at location [XX] and keep track of all reserved memory bytes manually, (or write down the reserved memory addresses on a sheet of paper), because the current program counter (technically PC+1) is saved at that location [XX] specified as argument of JMD, and then the Jump portion of the instruction actually sends you to location [XX+1] instead of the more intuitive & expected [XX] provided. After some logic is done in your "subroutine", you may instruct "JPI [same mentally‑managed XX address]" to return to wherever you were before. And, if all that is understood, programmers were also put on notice of a potential pitfall: if using an "Unconditional Jump" instruction, it is still essential to specify a valid "Condition" Value, otherwise it won't be a Jump Instruction at all anymore...!

In the entire exercise of attempting to use JMD effectively for implementing subroutines, one of the very few precious bytes of available memory are wasted. Memory address [XX] consumes the byte, which is an important loss since there are only 256 bytes available to do everything...! (minus 9 that are reserved for special functions and might be dangerous to reuse).

Rather than use the "Jump and Mark" feature, which requires the programmer to maintain a paper‑database of reserved memory addresses anyway, if all we do is use JPD "Jump Direct" for all jumps, we can save several bytes across the program, potentially making the difference between whether or not our software is possible.

Compounding the issue, the KENBAK relies on there never being more than 256 bytes of accessible memory, or else a language revision would have been needed. There is no room for expansion without significant redesign, which can be said to be not a very "inspirational" design for engineers and developers of the future.

The JMD instruction, one of the few instructions that do exist, is functionally useless in most common cases. However, it should be noted that JMD is equivalent to the 1965 PDP-8's JMS instruction. JMD is not an invention of John Blankenbaker, but instead an established industry standard of its time. However, on that platform, it is touted that JMS prevents unintentional reentrancy, which is not a benefit for the Kenbak‑1 since it does not support interrupts. Also, on the PDP-8 memory is expandable, so it hurts less to "waste" a little bit of memory storing the return address.

JMD's inclusion on the Kenbak was really only useful for educational purposes. Exercises based on it were in fact included as part of the educational materials prepared by Blankenbaker. It was a way to let students get used to the structure of "subroutines" as implemented on prior microcomputers that were more capable and able to use the structure usefully.

Compare though, JMD to the structure of subroutines as implemented in the article‑contemporary 8008 microprocessor (April 1972, only 11 months after the KENBAK released). We actually save a byte using that easier‑to‑manage structure, since on that platform, the "Stack" is built into the CPU, saving a byte in memory that would otherwise need to hold the address of a second jump, and also, because there is a whole suite of single‑byte CPU return instructions (RET, RFC, RFZ, RFS, RFP, RC, RZ, RS, & RP) saving an additional byte in program memory by not having to specify some second indirect return address value, as was necessary on the KENBAK. And of course, the 8008 can address a lot more than just 256 bytes of memory.

What Blankenbaker did with what was available, when he did it, and at that pricepoint, it is an impressive machine that should have seen more success, for at least 1 year. The truth is though, the KENBAK-1 was not an "inspiration for many engineers and developers" as sometimes touted. It had no expansion slots, no external I/O interface, no realized ability for expansion in any way, and even in the context of computing in the early 1970s, was considered a machine too limited to be truly "compatible with microcomputer application goals".

This unkind, unfortunate, and extremely brief citation might have been the only surviving industry opinion of how the KENBAK‑1 should be remembered, if not for what happened over a decade later.

If the Kenbak-1 was not historically remarkable, easily forgotten, and "incompatible with microcomputer application goals", then why would it now be considered the First Personal Computer?

It turns out that the story of "How the KENBAK‑1 won the title of First Personal Computer" is a lot more historically interesting than the machine itself.

In October 1985, the Boston Computer Museum[who?]Short history: "The Computer Museum", (sometimes known as "Boston Computer Museum", "Computer Museum of Boston", or "TCM"), started in a broom closet at DEC in 1975. The collection grew and grew. Eventually, between 1996 and 2000, the board decided to move most of the collection to Mountain View California, forming the modern day Computer History Museum. However, a few artifacts remain in Boston, at the Museum of Science (Boston). began advertising an actual "Contest" world‑wide in several magazines published by CW Communications, a publisher touted by the museum to be "the largest publisher of computer trade magazines in the world". The contest was also advertised in the tenth anniversary issue of BYTE magazine, gathering a lot of attention in the tech community. Advertisement of the contest concluded 6 months later in March 1986, with the results announced in Fall 1986. The year 1987 is sometimes reported (e.g. by the BBC), but nothing actually happened in that year, other than perhaps wider circulation of the results.

Forgotten now, the contest was not actually mentioned to be seeking the "first personal computer" as has been later assumed. That title was never advertised to have been at stake. Rather, the advertisement was written in the style of a "WANTED" classified section advert, soliciting that those who had been involved in computers for a long time please donate their "kit computers, programs, newsletters, etc. from the days of the first hobbyists and hackers, including early serial number pre-1980 machines and first releases of operating systems, languages, and applications programs". The advert does mention the term "Personal Computer" several times, but it is not the sole focus communicated. 320 offers of early-computing artifact donations were received, of which 137 were accepted, a great success for the museum.

Despite being apparently just an appeal to donate artifacts to be preserved at The Computer Museum, it was explicitly defined as a "contest". The details were:

"Donors of the five best finds will receive all-expenses-paid trips to Boston for the resulting exhibition's grand opening party" [...] "Entries will be judged on significance, date, rarity, completeness, and condition. Donations are tax-deductable."

As defined, it could not have been known that this 1986 "contest" would go on to crown the Kenbak-1 as the "World's First Personal Computer". It could not have even been known that there would be a first prize awarded. It simply sought to award five plane tickets to Boston, to thank those who donated "the best" objects, and to take a picture together at a ceremony. There was no way to enter the "contest" of "earliest personal computer" without actually donating a historical object (with no advertised guarantee you could have it back), and "earliest personal computer" was also not an announced category prior to the contest's conclusion.

This "Wanted: Old Thinker-toys" donation drive having occurred in 1985 and 1986, some 10+ years after the first uncontroversially "Personal" computers, seems to have occurred at just about the right moment in time where these objects would not yet have been considered "Vintage and Historical" ($$$), but instead considered "Dusty and Taking up Space" based on my own modern observations. Indeed, the advert put out in CW Communications published magazines describes them as much.

It was therefore extremely smart and fortunate for this donation drive to have occurred when it did. It is still to the public's benefit today that it occurred, decades later. Not only did TCM save many historic machines from landfill and still continue to display them (now in California), but having done this donation drive in the relatively-early year of 1985 is amazing. They were genuinely able to preserve part of computing history by soliciting early technical computer magazine readers of the world to please send anything they thought was both historic and related to computers to be preserved at their museum. If one could go back in time to 1985 with the sole mission of preserving early computing history, with all the modern hindsight available today, it would be difficult to do much better than TCM did.[note]At least in terms of spreading word that their museum existed and would like to preserve early-computing artifacts, it would have been hard to distribute that news widley to the most relevant candidate donors better.

That said, I would guess that if the Computer History Museum today had the opportunity to re-evaluate the 183 computing artifact donations denied in 1986, they would gladly accept many more of them now. Perhaps reevaluation could have been done in the 1990s, 2000s, or even still today, approaching the 40th anniversary of Boston Computer Museum's event.

It's possible that a few of these previously unaccepted donations still exist in the hands of those willing to part with them, though it's definitely now in most cases too late to gather the artifacts without the hangup of their increased monetary value which has surely accumulated over time. It would often be difficult to contact these people (or their descendents...) based only on their name and the address they had in 1985/1986. It may yet be possible though, 40 years on, to attempt contact.

In particular, I was a bit troubled by their response to the only mentioned denied artifact:

"Perhaps the most bizarre offer came from Argentina — a manuscript dating from around 1800 containing a card punched with holes. Said to be from Marie Antoinette imprisoned in the Bastille, it contained a coded message to her supporters outside the prison. Overall the response from abroad was disappointing [...]".

Marie Antoinette was executed in 1793, making a coded message purported to be written by her on punched card among the earliest known examples of this data storage method (if genuine).

This sounds like a very worthy artifact to be included in a museum, even able to find a place in a more specialized Computer Museum, but unfortunately, there is no artifact similar to this that I could find in Computer History Museum's catalogued collection today. Their contemporary characterization of this donation offer as "Bizarre" and "Overall Disappointing" is unfortunate. I hope this artifact made it into a museum somewhere, but in a cursory search, I was not able to find any information on such a document written by Marie Antoinette anywhere online.

It apparently just wasn't what TCM was looking for at the time, even though it does fall into the category of "pre-1980 records" solicited. Today, I think an artifact like this would fit very easily into Computer Museum of America's "Punched Card" area, which displays a timeline of the storage format going back to the year 850, and features an authentic portable Jacquard Loom. The Computer History Museum in California also maintains many items in their catalogue related to this storage format, such as the Jacquard Loom, the Hollerith tabulating machine, and IBM 029 Punch cards.

Hindsight is sometimes difficult to consider. It is the case in many preservation efforts that we make mistakes that are only later realized and regretted. I'll end this tangent on a happy note though: the Boston Computer Museum and its continuation at the Computer History Museum in California have generally done an excellent job in the active preservation of computing history as it happened, this donation drive only one of many examples of their proactive efforts, "most ideal outcomes" nonwithstanding.

However, in announcing the results of the "donation drive / contest" in the museum's own "Computer Museum Report" (Fall 1986), the characterization of the event changed:

- The contest (now over) was officially renamed from "Wanted: Old Thinker-toys" [CW Publications][note]Titled "Wanted: Early Personal Computers, etc." in [BYTE magazine] to "The Early Model Personal Computer Contest"[Computer Museum Report]. This may have seemed at the time like an inconsequential change to better set the stage for all the chosen winners of the "five best finds", but it has dramatic consequences in contextualizing who would have entered the contest, and how the contest would be remembered in the future. While previously, it was characterized that "date" was just one of the many criteria that would be considered in determining the "five best finds" (which included software and documentation), at the same time the contest was announced to have ended, the contest shifted to "early date" being the primary criteria and explicitly "personal computers" were the only contestents.

- While telling the story of the entire event from conceptual stage to its final outcome, presenting a complete narrative of the event to be remembered, the Boston Computer Museum did not emphasize very much that the contest was really presented as a general artifact donation drive. Instead, the story was written in a way that was more likely to present the museum as a respected and established authority. This was not done maliciously, as it is in-fact still mentioned that the original heading was "Wanted: Old Thinker-toys" and it is clear in the article that the "somewhat unusual collecting event" was a type of donation drive to "remedy the situation" of "gaps in our collection" "before the early machines disappeared". Good faith must be assumed, while also recognizing that the original contest description was not included in the museum's own reporting of the event, and this would affect how the contest was remembered.

The results of the contest are spoiled by the premise of this article, but the museum's exact words are important in understanding what happened next:

"We awarded the first prize to the 1971 Kenbak‑1, submitted by its creator John Blankenbaker. This small machine contained an eight‑bit processor built up from medium‑scale and small‑scale integrated circuits, and qualified as the earliest personal computer known to the judges."[Computer Museum Report - Fall 1986 issue]

There were three judges: Steve Wozniak (a very famous name, engineer & cofounder of early Apple Computer), David Bunnell (worked at MITS when the Altair 8800 was invented (in marketing), worked directly with Paul Allen and Bill Gates in 1975, publisher of PC World Magazine at the time), and Oliver Strimpel (executive director of the Computer Museum of Boston).

In a very engineer‑like way, they qualified that the KENBAK‑1 was merely the earliest personal computer "known to the judges". Given the authority of those involved, it makes sense that this qualifier was forgotten. Rather than forget that disclaimer though, it should instead be further disclaimed that the Kenbak-1 was only the earliest personal computer known to the judges in 1986 (as reported by Oliver Strimpel in the context of the contest) and may not necessarily represent their later historical opinions. (We'll touch on this later.)

Over time, the title awarded on that day, which was not a previously announced category and was only possibly available to have been won by those who permanently[note]It is sometimes suggested that people could have paid return postage to have their machines returned to them after the contest. Perhaps this was even done (though there is no detailed case of this known to me). John Blankenbaker is quoted as saying it could "maybe" have happened.

However, there is no guarantee that you may have your machine back written in the contest advert, and it is clearly against the advertised spirit of the donation drive. I suspect that if return of machines ever happened, it was for a very small amount of ridiculous people who begged the museum, or harassed them, and not the norm. It is not what any normal person would expect when donating items to a museum. donated their machine towards a contest that was actually presented as a Wanted advert, has now morphed into the Kenbak‑1 being the professionally considered the "First Personal Computer" period, with seemingly no mitigation from any modern authority.

History is mutable and our understanding of it regularly changes, when facts not previously considered are then made apparent

Ironically, it could be said that the Boston Computer Museum's 1986 contest was advertised a lot better than the computer that actually won it, and was much more influential as well. In the same way that the Boston Computer Museum changed the history of personal computing by writing the Kenbak-1 into a timeline which would have naturally forgotten it, it is still possible to reconsider the Kenbak's sometimes inaccurate overemphasis.

It may have genuinely been the best effort possible in 1986 in determining the First Personal Computer, having publicised the contest to the extent the Boston Computer Museum did. However, any representative who did not literally submit their computer to the museum could not have entered and possibly won. There was also the potentially controversial rule that "In defining the personal computer, we excluded plastic or cardboard educational and toy kit[s ...], as well as programmable calculators." which some people may disagree with, both then and now.

Looking at the question of "First Personal Computer" today, now with the benefit of online indexed magazine databases and digitized sales catalogs, it is relatively trivial to find examples of Personal Computers that predate the KENBAK‑1. There are at least a dozen prior commercially available computers that were "Inexpensive & Portable" enough to be considered "Personal" while also possibly being "Capable" enough to be considered a "Computer". There are even several prior candidates that were Turing Complete "real" computers. Each one of those candidate machines have interesting possible explanations to speculate on the answers to: "Why was this not donated to the museum for consideration? Why would it not have won the retroactively named 'Early Model Personal Computer Contest'?"

A more accurate legacy for the Kenbak computer

Our modern hindsight leaves the KENBAK‑1 in an awkward position:

"This is the First Personal Computer!... Except for this one to the right of it, which might also be a Personal Computer... Or is this one to the left of it might actually be the first really relevant Personal Computer? Hmm..."

It can be said of the KENBAK‑1 that it was a great effort in producing a more affordable computer predating the commercially available microprocessor, and that the finished product was profesionally prepared, well presented, and made in quantity. It is also notable for costing several thousand 1971 dollars less than most other candidate "First Personal Computers" that came before it, which should in fact be taken into consideration when determining if a "Person" could "Personally" own it.

Blankenbaker attributes the computer's market failure to the fact that he only advertised the machine in one magazine (Scientific American), and that he only attempted to target the educational market, which was "too slow and bureaucratic" to adopt his machine while it could have been relevant. He did not make a strong marketing effort to present the KENBAK‑1 to the "Computer & Amateur Radio Hobbyist" market, unlike the later more successful SCELBI‑8H and Mark‑8 computers, and also as the highly successful Altair 8800 did. By Blankenbaker's own modern recollection, it could be noted that the KENBAK‑1 was not really marketed for "Personal" use by individual "Persons". He modernly insists however:"In May 1971, I was thinking of private individuals. There's no question about it."https://youtu.be/OUCJXyThSXI?t=2555 [...] "We started thinking about: 'How are we going to sell these?' Well you know, reaching private individuals didn't seem so obvious. Actually in hindsight, it would have been easier, :-( than what we did do."https://youtu.be/OUCJXyThSXI?t=2710

Regardless of the original intention, in practice, the KENBAK‑1 was marketed and functioned as a competitor in the educational market. For schools, the Kenbak was an alternative to the option of timeshares of more capable and established computers, such as the PDP-8, which it had to compete against. Nearly all contemporary references to the Kenbak are from academic newsletters, announcing that the "KENBAK‑1 Educational Computer" was newly available, but then most of them never mentoning it again. This history in the classroom is evident even today. If you look closely at the KENBAK‑1 on display at the Computer Museum of America (identified as Nielsen6 on kenbak.com's registry), you can see where some student has taken a pencil, down from the data lamp "1" mark, around the bottom of the lamps 1 and 2, and scribbling off to the left. An act of graffiti common in schools, and the type of scribbling you might remember having done in youth, dragging a pencil alongside the ridges of a spiral-bound notebook.

_crop_denoise_lossy.webp)

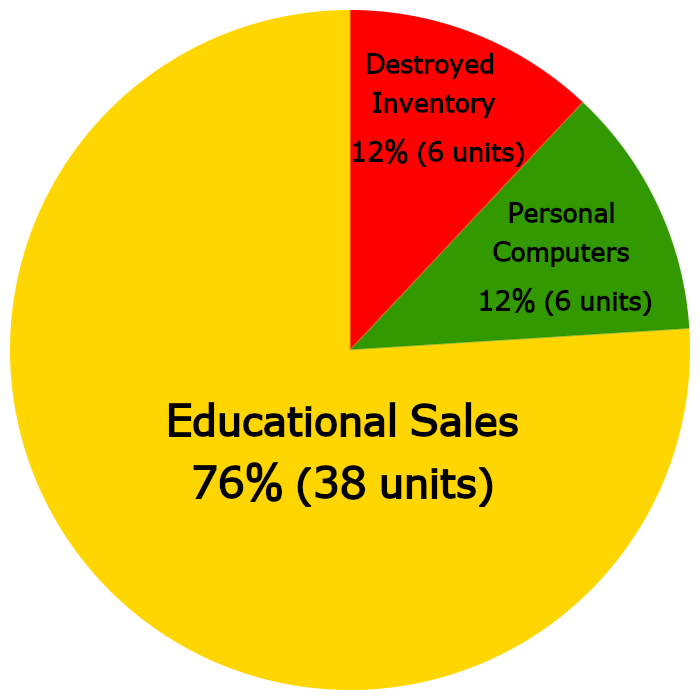

The Kenbak likely sold about as many units to individuals as prior "First Personal Computer" candidates did, even though they cost substantially more, because those earlier candidates were also much more popular. However, it's actually not entirely true that John V. Blankenbaker didn't make any attempt at all to reach hobbyists. His computer was mentioned in the Amateur Computer Society Newsletter in 5 different issues (though just twice during the timeframe that it could have helped sales). November 1971 was the first time the Kenbak was mentioned in that publication, but this only happened because "Information about a new educational computer, the Kenbak‑1, was sent by John Ranelletti, a new member in California." Blankenbaker was happy to speak to the publisher of ACS and gave more information, ultimately saying that unfortunately there couldn't be a less expensive kit option for hobbyists. In March 1972, Blankenbaker spoke with the publication again (a real effort specifically by Blankenbaker to contact hobbyists I think, unless ACS followed-up on their own accord), and in February 1973, ACS Newsletter said that "Half a dozen of the Kenbak‑1 (which is now $850) have been sold to private individuals, half of whom are programmers and EE's". This might be considered the peak relevant sales figure: 6 units sold expressly for Personal Use.

Of the 44 total units that were sold,[note]50 produced, 44 sold. Blankenbaker states that the unsold inventory was returned to him by CTI and then thrown away when he moved. (audience groans) the large majority of them were to sold to schools to be used as an educational aide. There are only 14 original units known to still exist.[note]There are two separate online registries for owners of Kenbak‑1 machines. There is kenbak1registry.com, and the more detailed and complete registry at kenbak.com.

The invention of the 8008 microprocessor chip very shortly after the Kenbak‑1's release (only 11 months later) obsoleted the machine before it could find wider success. The 8008 allowed the price of computers to roughly halve compared to the Kenbak, while also being easier to manufacture and being more accessible and usable to computer programmers.[note]The 4004 (also younger than the Kenbak) is not really relevant in the history of personal computing. Although it is credited as being the first single chip CPU, interestingly, it may not technically qualify for the distinction, since some Memory related CPU instructions have ignored data that is passed off to be handled by the intended companion memory chips instead. See the argument put forth at the section headed "Memory and I/O in the 4004" at Linux/4004

The 4004 is an unrelated design to the 8008, commissioned by a different company and intended for use in calculators. It is worth noting though that one insane genius was recently able to force the 4004 to emulate a more capable system, and boot modern Debian Linux, in September 2024. See their blog post at the aforementioned Linux/4004. Even from an educational standpoint, the Kenbak‑1 could have then been considered outdated, as processor instructions designed on the Kenbak to mimic systems that came before were no longer as relevant. The Kenbak‑1 was inspired by early antique machines that John Blankenbaker had worked on, like SEAC (1950), and Blankenbaker may have also taken inspiration from the freely available PDP-8 instruction set, as was apparently popular for early computer designers in the late 1960s.[note]This speculative statement is based on the similar structure of the Kenbak's JMD instruction and the PDP-8's JMS instruction. It is not clear if the PDP‑8 did actually influence Blankenbaker. The arrival of the 8008 microprocessor heralded a new era of computer programming, with its increased capabilities and a larger instruction set to wield, leaving the Kenbak‑1 behind perhaps only optimally useful for study as a Simple-As-Possible computer (but not as a basis for new computer design, per 1974 RCA).

Another contributing factor towards the Kenbak's lack of success: it is sometimes tempting to say of slightly later systems without screens and keyboards (such as the SCELBI-8H, Mark-8, and Altair 8800): "they could only be programmed with the switches on the front", but for the Kenbak‑1, it was unmitigatedly actually true. There was no expandability at all, not even a serial port to attach a teletype, output data from, or to control external devices like a printer.[one exception]One Kenbak ever, "Crosley", is confirmed to have been bought by an electrical engineer, who added multiple undocumented (and perhaps unfortunately, now removed) circuits, in order to add a teletype interface (both input and output). He had many other aspirations of extensions for the machine in 1974 as well, but instead bought a Sphere-1 computer the next year. (per www.kenbak.com) I have written more about the specific "Crosley" machine in a follow-up article here.

Crosley's machine aside, no teletype interface was actually officially planned.https://youtu.be/OUCJXyThSXI?t=4087 In 2016, John Blankenbaker recounted that professionals of the time said: "You've got everything here that every other computer has except input/output, and also I did not have interrupts. There's no interrupts here, that's a very important part... a very troublesome part too..."https://youtu.be/OUCJXyThSXI?t=2788 In that story, he does not recount having a come-back to this criticism, such as a promise that expandability was coming.

Interestingly, on most Kenbaks (but not on Nielsen1, Nielsen5, Nielsen7, Nielsen8, nor on the prototype "John1"), there is a suspect blank-slot on the front face of the Kenbak, which is usually closed and unexplained. John Blankenbaker also said in 2016 at VCF East: "If you notice here, and you can look later, there's a slot on the front panel, and the thought was that you might have a punch card you slide in and pull out, and it would read data, and that would be a quarter of your memory [64 bytes], so four cards might load your memory. [...] That was the only input/output extension that I thought of."

There was never a punch card expansion. It was teased to be available soon (for about $100) in the November 1971 Amateur Computer Society Newsletter, but appeared in no other marketing materials. In the March 1972 issue of the same Newsletter, it was explained that Blankenbaker had shelved the idea in favour of development of a cassette input. Then in the February 1973 issue, it was revealed that the cassette input expansion idea had also been dropped. It was explained by Blankenbaker in the February 1973 issue of the Amateur Computer Society newsletter that he had planned expansions, but these were dropped because "it isn't needed in the educational field, toward which the Kenbak‑1 is oriented."

Any way that you look at it, the story of the 1986 Boston Computer Museum's contest is an interesting one, in which the KENBAK‑1 ended up winning a starring role. However the KENBAK‑1 has a more difficult time today defending its title of "First Personal Computer", and until a telephone game was played, no one really proposed that it definitely actually was.

What was really the First Personal Computer?

The question is playfully entertained on the page http://www.blinkenlights.com/pc.shtml, an informative web page that gets most everything correct and has been impressively maintained in the exact same state and at the exact same location on the internet, almost completely unchanged, for at least 25 years. The page is so old that it actually co-existed with the Boston Computer Museum before it closed in the year 2000.

The webpage does manage to name most good candidates for the title, but notably missed out on at least a few, such as the Olivetti Programma 101 sold in 1964, which despite its calculator-like appearance, is a Turing Complete Computer. It was available at the "conceivably personally affordable" price of $3200 (about $32000 in 2024, adjusted for inflation). It's a stretch at that price if it could really be just for "Personal" use, but a lot of these machines were really bought, able to convince buyers that it was worth the price. Reasons varied. Some people needed them (NASA, for example, bought 10 in support of the Apollo 11 mission), some may have believed they were a less expensive option than whatever alternative there was, and some Programma 101 buyers would have been excited that it enabled them to do things that otherwise would not have been as possible, perhaps even as just a hobby, for Personal use.

As additional leverage towards considering a computer costing $3200 (1964 dollars) as ever having been for "Personal Use Only", (for comparison, the median income of all families in 1964 USA was $6600),https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1965/demo/p60-047.html consider the 1966 "Honeywell Kitchen Computer" mentioned on blinkenlights' page. It arguably has no conceivable communicated business purpose whatsoever and was clearly intended to be installed in the home, making its high price of $7000 (roughly $70000 today...) less convincingly an indicator that a computer of this price in the mid-1960s could not have been only for "Personal" use, at least among a few elite top‑earners. Perhaps the kitchen computer can be shrugged off as a joke advert no one is documented as having actually bought. Consider though how much it might be worth to be the only person in your city with a computer, positioned amongst all the other early pioneers and successful computer businessmen, if you had the foresight to recognize how powerful it was, and what a programmable computer enabled.

If you don't like that the Programma 101 doesn't have an alphabetical keyboard though, another missing contender is the Datapoint 2200. This computer was also earlier than the KENBAK-1, offering roughly 6 times the computer for 6 times the price. It was initially sold in May 1970 at $5000 (2 KB RAM version, approximately $40000 adjusted for inflation). It enjoyed a lot of success, selling a reported 4000 units by October of 1974, and enduring as a product until 1979. Unlike the Kenbak-1, this Turing Complete Computer actually did inspire billions of computers in the future, when Datapoint handed over intellectual property rights of the chipset built for this machine to Intel, which Intel condensed into the 8008 microprocessor (which became the 8080, the 8086, the 8088, the 80286, and on and on to today's Microsoft Windows machines). It is claimed that with some relatively small amount of translation, machine code written for the Datapoint 2200 would run on a modern x86_64 system today. There is a book about this computer titled Datapoint: The Lost Story of the Texans Who Invented the Personal Computer by Lamont Wood.[more on the Datapoint]The Datapoint 2200 was perhaps missed by the judges of the 1986 contest (first of all, since it perhaps wasn't donated), but also since it was sneaked past CDC's investment bankers not as a financially risky and unproven "Personal Computer", but instead as a replacement for the IBM 029 Card Punch (hence its stout 80 x 12 text display). It was never really able to perform that function, but was sold as a terminal instead, until one salesman discovered that it was actually a fully capable computer that could function independently (or so the legend goes).

The charade put on for the investment bankers that it wasn't a "real computer" apparently continued, even to this day being described on Wikipedia as a "programmable terminal usable as a computer". (Huh? What would that mean? Can't this accurately describe actually any personal computer with a serial port?)

The designer of the Datapoint 2200 later claimed that the machine was always intended to be a full-blown "Personal Computer" (a term that does have prior known usage), but I'm not sure how much Datapoint can be trusted on this claim, given the prestige associated with the title at stake, and given that Datapoint is notably sketchy. In this story, they admit to lying to their investors about what they were investing in, and the company also has a bad track record for truth established when it was "thrown into turmoil by an accounting scandal" starting in 1980 (lies to shareholders regarding actual profitability, a real-estate scandal in which a property was sold to two simultaneous parties, a hostile take-over by an outside party with the goal of shutting it all down, ... not exactly a reliable source)

One favourite candidate of mine, glanced over by blinkenlights in 1999 and likely disqualified for looking too much like a calculator by the Boston Computer Museum in 1986, is the HP 9100A (released in 1968). I took a deep dive considering this candidate, and really, if you consider all the expansions to what HP would later call the "System 9100", it is very legitimate in being considered a Personal Computer. With expansion, it was able to attach a full keyboard, communicate over serial, and draw arbitrary graphics on a plotter. Memory was also expandable, and there were other impressive expansion capabilities which in my opinion were not fully explored. Even without expansion, the HP 9100A was a Turing Complete Computer from the beginning. A convincing demonstration shows it was possible in software to write directly to the XYZ memory registers, poking arbitrary characters into display memory. Hewlett-Packard today bids it was in fact "the First Personal Computer", claiming that title on their enterprise website.

Blinkenlights' page concludes that Simon (1950) was the first personal computer, and while it could be a candidate, I personally disagree, since it is not Turing Complete.[note]It seems the punched tape used to process Simon programs is read sequentially, like a player piano. Simon is not documented to be able to jump backwards in a program. Without being able to jump to arbitrary segments of input programs (forward or back), it is not possible for Simon to be Turing Complete. In my mind, if it is not Turing Complete, it is not really a computer then. If we choose to allow computers that are not Turing Complete, then I would like to propose an even earlier Electronic Personal Computer invented over 140 years prior.

Assuming it's true that Simon has only two bits of memory, it might be said that an ordinary light bulb represents a computer only half as powerful as Simon. Although Humphry Davy, inventor of the Arc Lamp in 1809, likely did not realise that his invention would go on to be considered the World's First Personal Computer, it could be interpretted that his bulb represented 1 bit of digital memory. Connected to a light switch, as was common, it becomes "The Arc Lamp Computer" supporting mathematical addition. A binary value of "1" can be added to the bulb by turning the connected switch to the "ON" position, and you may even subtract 1 by moving the switch to the "OFF" position. The 1809 Arc Lamp Computer implemented an advanced memory protection scheme not common until centuries later, in that it is not possible to overflow or underflow the value in memory, no matter how hard a hacker may attempt to manipulate its switch. It would have been possible to extend the functionality of the Arc Lamp Computer by connecting its switch to a tape loop (as was done with Simon in 1950) and as previously implemented in the Jacquard Loom only a few years earlier. However, it's not known if Humphry Davy actually did meet Joseph Jacquard to complete the collaboration.[note]The fact of Simon being limited to "only two bits of memory" is possibly misreported. Consider: How can Simon display 5 light bulbs (I think there's actually 6) if his entire brain houses only 2 bits?

It seems like the "Selection" operation refers to what we might call "Banked memory" today, (a term more commonly used in the 1980s). See vintagecomputer.net for details. As a guess (without evidence of the following statement), perhaps the left three lamps display which bank of 2-bit memory is currently selected. This would bring the total to 16 bits of memory (but still only 2 bits addressable at any time).

The surviving example of a Simon 1 computer at the Computer History Museum in California visually appears to have quite a lot going on inside. 129 relays are claimed to be included in Simon's construction, each of which might be considered a binary state, though these would not all actually be addressible memory bits.

All this is to say, Simon was probably a bit more capable than I'm giving it credit for here. Unfortunately though, we really don't have definitive proof/demonstration of what Simon could do. To clarify, it is still unlikely that Simon qualifies as really much of a "computer" at all, since it is not suspected to have been Turing Complete.

Can we be even more obnoxious and abusive towards the definition of "Personal Computer"? What if we disregard the arbitrary requirement that a Personal Computer must operate on electricity? Then it might be said that the humble Counting Stick was mankind's first personal computer, some 20,000+ years ago. Clearly, we must draw the line somewhere, and I hope you do not draw it on a stick.

The "Most Correct" candidate for the title of "First Personal Computer"

The truth is that "First Personal Computer" is very much a matter of "Personal Opinion", and is not something that can be justly asserted as matter of fact.

That said, a case can be made that the "most correct" answer is probably the Altair 8800 (1975). The Altair is well supported as the rightful owner of the title "World's First Personal Computer" due to: its marketplace success, intended market of every-day people, proximity in time and direct role in leading to the beginnings of explosive growth and widespread adoptation of Personal Computers (now known as the "Personal Computing Revolution"), its long lasting influence (Bill Gates, S-100, etc.), documented historical impact (myriads of contemporary references), very cheap price relative to those that came before (and at much faster speed I might add), usage of a modern CPU on which billions of computers are still based on today (the 8080), availability of a wide selection of community created software and hardware, and probably several more good reasons.However, this question may be answered more accurately in the academic study of Linguistics and Etymology, rather than in consideration of Computer Science and its history in the household.

In The New York Times newspaper, the term "Personal Computer" was first printed on June 16th 1977https://www.nytimes.com/1977/06/16/archives/computer-show-preview-of-more-ingenious-models-computer-show.html, in interviews with two of the exhibitors of the 1977 National Computer Conference, in Dallas Texas. The New York Times reporter quotes Ryal Poppa, then-chairman of Pertec Computer Corporation[note]Pertec had just acquired MITS, about a month prior to the Dallas show, in May 1977. Pertec continued to sell the Altair 8800 technically unmodified, but under different branding, referencing the the Altair 8800 as the "Altair Personal Computer system". The same article also uses the term "Personal Computer" several other times, not in the context of Altair, but in interview with the chairman of Texas Instruments[note]Texas Instruments did not offer a personal computer in yet in 1977, but was involved in chip manufacture and calculators. They would release the TI-99 home computer in 1979., demonstrating its use as a generic term, and not only as an official brand name of Altair. A different New York Times reporter wrote an article shortly after, in August 1977, covering the "Computermania" exhibition in Boston Massachusetts. That article also included the term "Personal Computer" several times, perhaps more confidently in that there were not quotation marks around the term as often.https://www.nytimes.com/1977/08/26/archives/computer-shows-message-be-the-first-on-your-block.html

These usages are significant in that The New York Times is not a technical magazine for hobbyists or professional engineers. Its first inclusion in this prolific general-purpose publication demonstrates usage of the term reaching a more mainstream audience in the suspect year of 1977. It shows that by mid-1977, the term had reached greater maturity than when previously used as ad-hoc lingo in specialist publications. The term "Personal Computer" likely occurred in slightly earlier general-purpose publications/newspapers as well, but it so-happens that in The New York Times in particular, the term first described the Altair 8800.[note]The Altair 8800 was apparently initially rebranded as "Altair Personal Computer system" under Pertec, and later as the "8800b" and "MITS 300".

Pretty soon, (unfortunately for Pertec), the "Altair Personal Computer System" would seem long-in-the-tooth compared to new offerings in 1977 by Commodore[note]The Commodore PET was released in January 1977, the first of the "1977 Computer Trinity". Commodore owned MOS, inventor and manufacturer of the 6502 processor, allowing them to come to market before the others in the trinity. Sometimes, the Commodore PET is called the "First Personal Computer".

To its credit, it does have a screen and full keyboard, but so did the SOL‑20 (1976), based on the Altair 8800 combined with the VDM-1 (1975), a Video Display Module., Apple[note]The Apple II released just 6 days earlier in June 1977. Sometimes, the Apple 1 (prototype of the Apple II, 1976) is called the "First Personal Computer".

Wozniak (or his publisher) took credit for "Inventing the Personal Computer" in the title of his 2006 autobiography: "iWoz: From Computer Geek to Cult Icon: How I Invented the Personal Computer, Co-Founded Apple, and Had Fun Doing It"., and by Tandy-Radio Shack[note]The TRS-80 would be released in just a few months, in August 1977. Rarely, this computer I imagine might be called the "First Personal Computer" by those who owned it first. It was the cheapest of the three computers in the 1977 Trinity by about $100 over the PET and costing less than half the price of the Apple II. It was also very prominent, in that it was promoted by the ubiquitous Radio Shack stores that already existed nation-wide.. Although the Altair 8800 was outdated at the time that the term "Personal Computer" seems to have come into maturity and achieved more widespread use, the Altair was contemporary in 1977, and was perhaps the oldest computer using the label at that time (in other words, "The First").

What if we (unwisely) discount that we can only consider the term valid after it has stabilized and approached a more modern well‑understood and widely accepted definition?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (Second Edition, 1989), the term "Personal Computer" was first known to have appeared in the May 1976 issue of BYTE magazine. BYTE magazine also claims to have invented the term (along with many other computing terms),http://web.archive.org/web/20010701112713/http://www.byte.com/documents/s=132/BYT19990823S0001/index.htm and to their credit, would have been positioned to indeed play a significant role in popularizing the phrase "Personal Computer". Additionally, assuming good-faith, it is probable that BYTE magazine did independently invent this term, as it was not previously very much used, and it is a reasonably canonical construction to have independently occurred more than once.

However, the term "Personal Computer" was used prior in the advertising of the HP 9100A in 1968. This has been reported as being the earliest usage of the term by WIRED magazine, in an investigation done with the available digital resources in the year 2000.https://web.archive.org/web/20151004045031/http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/8.12/mustread.html?pg=11 I have independently confirmed in 2024: this usage by Hewlett-Packard may still be unique in being the earliest example of that term in the advertising of a Real Turing Complete System. So far, it is not evident that there is any earlier usage in that context.

The term did not first occur there either though. There was an even earlier usage of the term to describe a briefcase-sized analogue computer called the "SkeduFlo" (1962), which on the internet today is completely unknown and forgotten, (perhaps to the same degree that the Kenbak might have otherwise been).

"[...] The forerunner of the personal computer, a portable model which Dr. Mauchly calls "SkeduFlo", was displayed at the Plant Maintenance and Engineering Show in [...]"[The Science News-Letter, Vol. 81, No. 8 (Feb. 24, 1962), pp. 120-121] This system was invented by John Mauchly, whose earlier works include co-creating the much more remembered ENIAC, EDVAC, BINAC, and UNIVAC computers. Nothing more is yet really known about SkeduFlo, other than it was used to conduct specialized calculations at construction sites in the early 1960s. More information may exist, but it has not been digitized and made readily available online as of yet. If Mauchly did hypothetically invent something portable and programmable, worthy of being called "forerunner of the personal computer", he would not have been alive after 1980 to personally submit such a system to the Boston Computer Museum's 1986 contest (even if the system did still survive intact). His diaries and personal papers were instead donated to the University of Pennsylvania in 1981 and 1986 where they remain today, available only to those physically present there, perhaps holding more details about how advanced of an analogue calculator SkeduFlo really was, and if more than one was ever built.

Stretching earlier than that, it seems that "Personal Computer" was present as a niche concept in science fiction before anything resembling a personal computer actually existed. It is hard to confirm a "first year" in which that exact phrase was used on Google Books, due to many publications with miscategorized year, but consistently, it seems to be found legitimately in publications from 1962 and perhaps earlier. As a favourite early example of the personal computing concept in popular media, I'm very fond of the well-known depiction in the 1956 short story "The Last Question" by Isaac Asimov, in which the term "Personal Microvac" was more primitively used, in the context of the fictional Multivac computer.

What do you think was the First Personal Computer?

The historical fact of "first personal computer" is open for interpretation. Referring back to the blinkenlights article, the Altair was discarded with disdain:

"Unfortunately for computer history buffs, the Altair is often mistakenly called the first personal computer by Microsoft-loving journalists who don't know any better." (Historical Context, 1999)I actually don't fall into this category, having written this article on Debian Linux, a platform I've loved for many years...!Despite the convincing case presented above that from both a linguistic and practical standpoint, "The First Personal Computer" was the Altair 8800, this will generally continue to be a topic of debate and further consideration.[note]As a consolation, the Altair 8800 has sometimes been given the less-controversial qualified title of "First Successful Personal Computer".

It's important to note the historical context of when the Blinkenlights article was written. At that time in 1999, Microsoft was a popular target of hatred from the technical community, due to "Micro$oft's" anti-competitive business practices (which they later got in legal trouble for, see 2001 court case US vs M$) as well as Microsoft's leaked internal strategy of Embrace, Extend, and Extinguish. This was a very hot-topic item of controversy in the late 1990s, continuing into the 2000s, and in fact this documented historical strategy still taints Microsoft today decades later, re: skepticism of WSL Linux in 2016+ & GitHub acquisition in 2018+ "We Love Open-Source" 🤨.

Perhaps the author hoped that after the relatively recent success of Windows 95 and Windows 98, Microsoft would soon get their comeuppance and fade into history in disgrace (similar to Datapoint). If that had happened then, it would have somewhat diminished the importance that Bill Gates initially wrote Microsoft Basic for the Altair 8800. Instead, their Windows NT project was very successful in transitioning the Windows technology for an age beyond DOS, more stable and less prone to blue-screens, and they released Windows XP to great success in 2001 (after the blinkenlights article, but still before many people bought their first personal computer). With XP, Microsoft continued to play a foundational role as the provider of the software platform in which many people first experienced Home Personal Computers within.

With another 25 years of historical context, we have a wider and less controversy-clouded vantage point to appreciate the role that Microsoft played in those first waves of Personal Computing: both in 1970s/1980s computers running MS‑Basic and MS‑DOS, then in the World Wide Web era of 1990s Windows 9x machines. In fact, Microsoft still maintains relevance today (2024), with Microsoft Windows 10 and 11, and has further expanded themselves to the cloud computing space (Office 360, OneDrive, Exchange Online, Azure Cloud & associated services, etc...).

However, Microsoft failed to successfully transition to Pocket Computing in time with the Windows Phone (2010 - 2020, but limping from the beginning and enthusiasm gone quickly), which was a similar failed imitation of "what worked well for Apple" attempted by the Zune portable media player in 2006 (which did not meaningfully compete with the iPod).

It could also be said that Microsoft's attempts at detaching themselves from x86_64 have not been as agile and successful as Apple's transitions between CPU architectures, contributing to the modern loss of Windows laptop/desktop OS marketshare to Android/iOS and hemorrhage of the educational market to Chromebooks (much easier/less-encumbered OS to manage/control while also consuming less power and costing less than a PC based on Intel/AMD x86_64 CPUs).

If Microsoft is unable to build a satisfactory solution to continue maintaining decades old exes on a new ARM architecture, it seems likely that we will continue to see their increasingly-less-relevant desktop marketshare decline, until Microsoft is mostly known in just the cloud computing/business spheres, and not as much of a player in "Personal Computing".

Since the relatively early year in personal computing of 1986, new information and wider historical context seems to have been later considered by at least two of the three judges of the Boston Computer Museum's contest:

- Steve Wozniak co-authored a book in 2006 allowing the subtitle "iWoz: From Computer Geek to Cult Icon: How I Invented the Personal Computer, Co-Founded Apple, and Had Fun Doing It". It is a defensible claim, but not the strongest.

- David Bunnell's opinion also seems to have changed. While telling stories from his career in publishing and tech in a 40 minute talk at the 2012 Seattle Interactive Conference (fascinating talk with many anecdotes to follow up on, by the way), at 8 minutes 40 seconds in, David teasingly says:

[...] But as things developed at MITS — "MITS invented the Personal Computer", Duuuuh. How nice of them... — and so my job got a lot more complicated [...]

He says this unprompted, specifically addressing the controversy of "who was first", which is interesting. David Bunnell worked at MITS at the time that they created the Altair 8800, but Bunnell was not directly involved in its creation. He worked in marketing. - It's not known if Oliver Strimpel has reconsidered the "Earliest Known Personal Computer". He was Executive Director of the Boston Computer Museum until June 1998[note]https://tcm.computerhistory.org/Timeline/timeline7draft.htm, and seemingly had not changed his mind at that point, continuing to present the Kenbak‑1 as the "Earliest Known Personal Computer" at least until then. He could be contacted for comment if it's not possible to find a more updated opinion from him on this historic designation. He now seems to run a Geology podcast.

What about John V. Blankenbaker himself? At VCF East XI 2016, he gave this quote:

Any time you say "first", you gotta be very careful about your adjectives. First "what"? And so you had to be very careful. But it was selected, and other museums have continued the honor. The American Computer Museum in Bozeman, Montana, also has selected this as the First Personal Computer. And generally, it is recognized.

But if you ask me, I can tell you of some computers, that were before this. There was uhm, who's that famous toy company in New York City, with the high priced...? [...] Schwartz? That may be it! I was having some discussions about their taking, y'know selling this, and they were interested and they said, well one time, they had had a computer. It was very interesting, I don't know if any of you have ever seen this. It was a drum, it had pinholes, and you put tabs in there, that was 1s and 0s, and the drum rotated *gesturing* ooone, and the tabs then were in position, that defined the next operation, you know, it was automatically sequenced...! That was a computer! That was before this! But it didn't get a lot of recognition... at all...

Again, it's a problem of how you define your adjectives that you use to describe it.

He is pleased to be recognized for the honour, but honestly acknowledges that it is not "The First Personal Computer" full-stop, needing further explanation with explicitly defined adjectives in order for it to qualify.

There are many good answers for "What was the First Personal Computer?", and the related question of "Where did Home Personal Computing really begin?" Some candidate machines have roots even earlier than the KENBAK‑1 and some arguable candidates came later as well. At the $750 price point, perhaps the KENBAK‑1 can still be chosen as "The First Sub-$1000 Turing-Complete Personal Computer", (unless it is discovered that some earlier computer also meets that criteria and more qualifiers need to be added for the Kenbak to be "the first" at something).

I'd be very interested to hear what your favourite candidate for the title is, particularly if doesn't happen to be any of the "First Personal Computers" mentioned here.[note]Shout out to the MCM/70, believed by all True Canadians to be the "first usable personal microcomputer system". 🇨🇦 🦫

You may email other comments to [email protected]